By Jennifer Leask

For some people living in Haida Gwaii, better internet connectivity and local economic development go hand-in-hand. The efforts of these tech-savvy islanders aren’t focused on catching up with urban residents – they are about taking the lead.

Patrick Shannon is one of those people. The 26-year-old Haida man grew up in Skidegate, one of the communities in Haida Gwaii, an archipelago of islands off the Northwest coast of British Columbia. While there are more than 150 islands in Haida Gwaii, the entire population is distributed between the two largest ones. Shannon uses the creativity that he says he learned through his First Nations culture to build a successful media design business. After a stint working in Vancouver, he returned home and is now putting his efforts into using digital technologies to transform the local economy. He’s been widely recognized for this vision, most recently being named the 2015 Young Entrepreneur of the Year at the .

Patrick Shannon and Yolanda Clatworthy at the opening of X̱aayda Hub in July. Courtesy Patrick Shannon

Shannon, along with Yolanda Clatworthy, co-founded , a “co-working space, collective, and launchpad” for creative locals who want to strengthen local economic and community development. They met in 2014 and she recently moved to Haida Gwaii from unceded Algonquin Territory in Ontario. They shared a vision for creating a “social innovation hub” and opened X̱aayda Hub in July.

“My dream, my goal, is to see Haida Gwaii be the technology hub of Northern B.C.,” he told firstmile.ca.

“It’s an amazing place to live. People move here for the lifestyle and to be able to pretty much be able to do what ever you want to do. Because so much of the work we do these days is done on computers, if we can make it so you can do that work from Haida Gwaii, we can attract amazing people, we can retain amazing people.”

The grand opening party of X̱aayda Hub. Courtesy Patrick Shannon.

In recent years the population of Haida Gwaii has been declining, in part due to jobs lost as island employment moved away from a resource-based economy. The population was more than 5,000 not too long ago, but now at 4,300 (a loss of about 15 percent), it’s clear that something has to change to entice residents to stay. True to the self-sufficient character of the island population, the communities are working to come up with an innovative solution themselves.

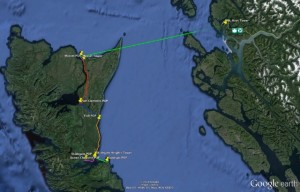

GwaiiTel is one piece of that puzzle. Created as a not-for-profit society made up of three municipalities, two Band councils, two unincorporated areas and the Council of the Haida Nation, GwaiiTel worked to find funding to build the infrastructure that would bring a broadband signal from a tower in Prince Rupert, 185 km away on B.C.’s northern coast. Today, GwaiiTel brings broadband to those two islands through this connection as the provider and aggregator of wholesale transport bandwidth services. The society then resells this bandwidth to local Internet Service Providers (ISPs) which service homes and businesses.

Network map of GwaiiTel. Courtesy Carol Kulesha.

The Mayor of Queen Charlotte city at the time, and GwaiiTel Chair Carol Kulesha, was one member of GwaiiTel Society working towards securing project funds. She reached out to the , a fund whose goal of developing a sustainable island life includes infrastructure projects like broadband, as well as to provincial and federal grant programs. As with most projects in Haida Gwaii, Kulesha explained, the islands’ communities had to collaborate to find a solution to the connectivity problem.

“We are not an easy place to build: we are spread out, we don’t have a lot of people, we have a challenging topography. Just trying to cross the Hecate Straight with a signal is huge. Trying to connect communities when you have mountains and trees, and in some places another body of water, is hugely difficult,” she said.

Many people on the islands work remotely, Kulesha said. For example, a forestry company can be based in Haida Gwaii yet be remotely involved in planning projects in Africa. With limited bandwidth it is hard for them to stay because things like maps and photographs are too hard to send, but “as we get better [Internet], more of them can stay [and work here].”

“We have been steadily losing people and we are losing our children…we need to be able to ensure they have a way to make a living where we are.”

Shannon said most young people who leave Haida Gwaii for school never return. He recalled how when he did come back to Skidegate, he had to give up many of his Vancouver clients because he couldn’t send videos or photographs over the Internet. Instead, he had to physically send these materials through the mail. In Haida Gwaii, mail only leaves the islands twice a week – sometimes even less often, if weather delays the ferry.

A photo of a beach in Skidegate. Courtesy Patrick Shannon.

While the connection is improving, Shannon says the bottlenecks still make his work challenging during peak hours of the day. But he believes that it will improve soon as GwaiiTel completes the latest upgrades to the network by putting in a redundant set of radios on their towers, and providing a fibre backbone connecting the communities. This project will offer more stability and consistency.

With the connectivity problem almost solved, the next hurdle for the island’s residents, according to Shannon, is affordability. There is no such thing as an unlimited internet package in Haida Gwaii, and overage fees for data can be prohibitively expensive. Due to his high Internet use, Shannon says his bill is between $200-500 each month.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Kulesha is optimistic that Haida Gwaii’s residents will find a way to work through that challenge. GwaiiTel is currently looking for funders to improve their service and bring down costs. She’s also hopeful that the society’s non-profit broadband model can play a part in improving connectivity infrastructure and services for other rural and remote communities.

“If we were part of a bigger plan for Coastal communities, that would be tremendous.”

This community story was produced with the support of a from the (CIRA).