So what do we mean when we talk about ‘broadband-enabled applications’?

People can shape broadband networks and digital technologies into a variety of tools. As discussed in our overview of the social shaping of technology in Topic 4, technologies do not spring forth fully formed, but rather are malleable and can be (re)shaped to meet our needs.

The First Mile website is one source of stories that showcase how First Nations are developing broadband-enabled applications. One set of stories provides ‘how-to’ guides that community members can use. For example, consider videoconferencing, which uses voice and video to enable real-time, interactive communication between people located in different locations. Using broadband links to support instant video connections helps reduce the barriers of distance that can be a challenge for individuals and groups in regions where travel is expensive or difficult. For an overview of some of the benefits of this application, read an article by Lyle Johnson, the videoconferencing coordinator at KO-KNET services.

While videoconferencing is one application that First Nations are using to communicate, other options exist. One alternative is Skype. One innovative use of Skype is a project undertaken by K’atl’odeeche First Nation in the Northwest Territories. There, the Band Council uses Skype and radio links to broadcast meetings to community members who cannot attend in person. Henry Tambour shows us how to set up a Skype system to broadcast community meetings.

As well as connecting with community members, broadband applications enable First Nations to communicate with one another on a regional basis. For example, the Council of Yukon First Nations established a videoconferencing network. Although the program started with health services, it has since expanded to include a broad range of uses. Read about this initiative. A similar example of First Nations using videoconferencing networks on a regional basis is the First Nations Education Council’s work in Quebec.

Ongoing technical issues limited broadband-enabled applications

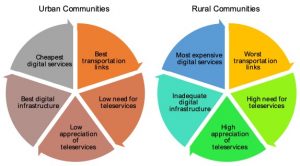

Unfortunately, challenges that limit the ability of people living in rural, remote and Northern regions persist. For example, data caps block or limit many remote communities from accessing digital applications like videoconferencing and cloud apps. A 2018 article by Susan O’Donnell and Brian Beaton describes the paradox of telecommunications development in remote regions — the image below presents a visual summary of this concept.

Geographic paradox of telecommunications development (O’Donnell & Beaton, 2018)

While the “rural penalty” associated with telecommunications is a well-recognized challenge (e.g. Parker, Hudson, Dillman, Strover & Williams, 1995), O’Donnell and Beaton’s framework is unique given its specific focus on remote communities that require connectivity to access essential public and commercial services, yet are dependent on for-profit providers that often fail to provide service levels required for such access. Their work suggests access inequalities in remote communities reinforce one another in different ways than in urban communities. For example, remote communities have limited access to large schools and hospitals, while many urban residents have a lower need and appreciation for teleservices because they can choose to access those services in-person (recognizing that urban residents – particularly elderly persons and persons with disabilities – may also face challenges accessing such services). The framework also shows the dynamic relationships between different forms of digital inequality present.

Such continuing issues show the importance of working with local partners to provide solutions that actually meet their needs. Innovative uses of broadband-enabled applications in Indigenous contexts can illustrate the potential that comes alongside the availability of adequate, affordable, accessible, reliable infrastructure and services.